Sea kayaking is what we do. We paddle for the adventure, beauty, and solitude on the water, but it also carries inherent risks. Every trip on the water may expose the paddler to dynamic and sometimes unpredictable hazards. Successful sea kayakers are not just skilled paddlers; they are also thoughtful risk managers. By developing a mindset of risk assessment and mitigation, paddlers can make informed decisions that maximize safety while still embracing the joy of exploration. Risk assessment and mitigation is not just for trip leaders. Every paddler must have the ability to make their own decisions and use their own judgement every time they go out on the water.

Defining Risk: Likelihood and Consequence

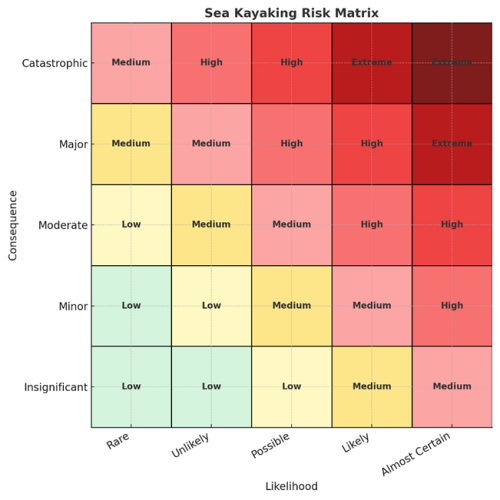

Risk in sea kayaking can be defined as the combination of two factors: The likelihood that something unexpected that might be bad will happen combined with the severity of the consequences if it does. Simply defining risk as the possibility of something bad happening could significantly reduce our options for fun and adventure.

By combining the two factors we can distinguish between minor inconveniences and serious threats. For example, capsizing alone may not be a high risk situation if conditions are mild, the water is warm, and we are paddling with a group of experienced paddlers, the consequences are low. On the other hand, capsizing offshore in 50°F water with rough conditions and high winds has much more significant consequences.

Understanding this balance between probability and consequences is the essence of risk assessment. Every paddling trip involves tradeoffs, and every decision we make, what route to take, what gear to carry, whether to push ahead or turn back, shifts where we stand on the risk spectrum. In addition, we all have our own interpretation of what is an acceptable level of risk.

The Elements of Risk in Sea Kayaking

Several categories of risk consistently appear in sea kayaking. Breaking them down makes them easier to evaluate:

- Environmental Risks

- Weather: Sudden squalls, thunderstorms, or strong winds can quickly escalate conditions. Offshore winds may push paddlers out to sea, while onshore winds can create steep, breaking waves.

- Water conditions: Tides, currents, and swell patterns affect travel speed and stability. A tidal race or eddy line can flip a kayak in seconds.

- Temperature: Cold water immersion remains one of the most significant hazards. Even with proper clothing, hypothermia can set in within minutes.

- Visibility: Fog or darkness can make navigation difficult, increasing the risk of becoming lost or colliding with other boats.

- Human Factors

- Skill level: A paddler’s ability to brace, roll, navigate, and rescue makes all the difference.

- Experience: Beyond raw skills, judgment develops with time on the water. Novices may underestimate risks or overestimate their capacity.

- Physical Condition: Fatigue, dehydration, or injury can degrade decision-making and performance.

- Group Dynamics: Peer pressure, poor communication, or mismatched skill levels in a group can create unnecessary hazards.

- Equipment Risks

- Kayak design: A short recreational kayak may not handle surf or open crossings well.

- Gear reliability: Broken paddles, missing spray skirts, or inadequate clothing can transform a manageable capsize into a serious emergency.

- Safety equipment: Lacking essentials like a pump, paddle float, tow line, or VHF radio increases vulnerability.

Recognizing these categories doesn’t eliminate risk, but it sharpens awareness of what could go wrong and why.

The Risk Assessment Process

Risk assessment in sea kayaking is an ongoing cycle before, during, and after each trip. In order to mitigate risk, we must first be aware of the risk. Some levels of risk may be unacceptable even with mitigation.

Step 1: Pre-Trip Planning

This is where the bulk of risk mitigation happens. Thoughtful preparation sets the stage for a safe experience. Key questions include:

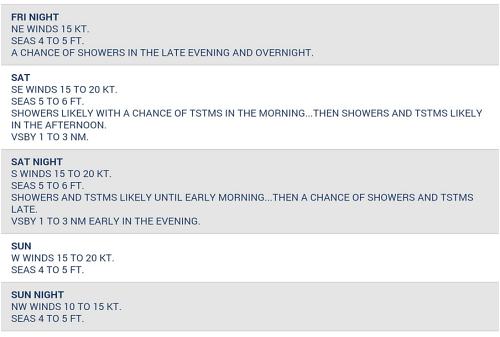

- What are the weather and tide forecasts?

- Is the route appropriate for the group’s skill level?

- Are escape points or bail-out options available?

- Is the equipment in good condition?

- Do we have the right clothing for immersion?

Trip leaders often use the “What if?” test: What if the wind doubles? What if someone capsizes and cannot roll? What if fog rolls in? Imagining these scenarios in advance allows for proactive solutions.

Do you want to go paddling Saturday?

Step 2: On-Water Awareness

Once on the water, conditions can change quickly. Risk assessment becomes dynamic. Paddlers should continuously scan the horizon, monitor group energy levels, and compare reality against forecasts. Are storm clouds building. Do whitecaps begin forming earlier than expected. These are signs to reassess whether to continue or turn back.

Step 3: Decision Points

At critical junctures, entering a tidal race, committing to a crossing, or choosing whether to land through surf, paddlers must weigh the likelihood of trouble against the severity of the consequences. If both are high, the prudent choice may be to wait, reroute, or retreat.

Step 4: Post-Trip Reflection

Every trip provides learning opportunities. Discussing what went well and what could be improved builds judgment for future outings.

Risk Mitigation Strategies

While we cannot eliminate all risks, we can reduce both their likelihood and consequences.

Reducing Likelihood

Training and Practice: Regularly practicing skills such as rescues, rolls, and navigation reduces the chance of small mistakes developing into emergencies.

Choosing Conditions: Selecting venues that match skill level lowers exposure to hazards. Beginners may thrive in sheltered bays, while advanced paddlers may deliberately seek surf zones to refine skills. Don’t be afraid to make last minute changes if conditions deteriorate or if paddlers are having an off day.

Maintaining Equipment: Inspecting kayaks, PFDs, and communication gear before trips reduces the likelihood of equipment failures.

Managing the Group: Paddlers need to be informed regarding the nature of the paddle, the pace, and decision points. Communication is established including agreement on signals, VHF usage, etc.

Reducing Consequences

Dress for Immersion: Wearing a dry suit or wetsuit appropriate for the water temperature buys precious survival time in a capsize.

Safety equipment: Have the necessary equipment to manage emergencies. Carrying bilge pumps, paddle floats, spare paddles, tow ropes, and first-aid kits helps the group deal with incidents and reduces the severity of consequences. Radios, PLBs, or cell phones in waterproof cases provide lifelines.

Paddle with Pals: Paddling with a group of experiences paddlers multiplies rescue options and reduces isolation.

Plan for the Worst: Knowing exit points, shelters, and procedures for contacting help limits how bad “bad” can get.

Call for Help: Call for help when you need it. The coast guard would much rather perform a rescue than a recovery. Don’t wait until you are out of daylight or are so exhausted that you can’t participate in a coast guard rescue. Learn the protocols for communicating with rescue teams and participate in training when possible.

Balancing Adventure and Caution

Some paddlers worry that focusing on risk diminishes the spirit of adventure. In reality, the opposite is true. By systematically assessing and mitigating risks, we create the space for adventure. Confidence in preparation allows us to embrace challenging environments with resilience rather than anxiety.

Consider a group of paddlers launching into choppy seas on a windy day. Water temperatures are in the upper 50s. The paddlers are wearing dry suits, PFDs, and spray skirts. All have practiced rescues. Several members of the group are carrying a VHF radio and spare paddles. The group has charts of the area, they know the tide and current predictions. They may still capsize, but the consequences are minimized. These paddlers can push boundaries responsibly, knowing they have the tools to recover.

A second group plans a paddle on the same day. They have never practiced rescues, are not dressed for immersion. Some may be in recreational boats with minimal flotation. They are unfamiliar with the tides and currents in the area. This group of paddlers are at high risk of something going wrong, and the consequences of a capsize in these conditions are much more severe. They may be looking for adventure but they may also get more than they can handle.

The Role of Judgment

Ultimately, risk assessment is as much art as science. Charts, forecasts, and safety gear provide data, but judgment integrates it all into real-time decisions. Good judgment often means turning back before reaching the planned destination, or choosing not to launch at all. Experienced paddlers learn that discretion is not failure; it is wisdom earned through humility and respect for the sea.

Conclusion

Sea kayaking is an adventure sport where beauty and danger coexist. By defining risk as the interplay of likelihood of an event occurring and the consequences of that event, we gain a practical framework for decision-making. Systematic risk assessment, before, during, and after trips, helps paddlers recognize hazards, evaluate tradeoffs, and prepare accordingly. Risk Mitigation strategies, from skill-building to equipment choices, reduce both the probability of incidents and the severity of their outcomes.

In the end, risk management does not limit our experience of the sea; it enhances it. With awareness and preparation, we can paddle further, explore deeper, and do so with confidence that our adventures will be memorable for the right reasons.

Paddle Safely,

Paula Hubbard

CPA Coordinator

Share This